The headquarters of the Chicago Police Department as seen from a ninth floor apartment in 3542-44 South State Street, a recently demolished high-rise at Stateway Gardens.

By Jamie Kalven, published in The View from the Ground in March, 2003.

Chicago Housing Authority representatives constantly sound the theme that public housing residents are citizens of the City of Chicago with equal claims on the services available to other citizens of the city. This attractive proposition resonates to principles of justice and equality. It evokes a new day for public housing communities long abandoned by the institutions funded to serve them. It has also been employed as the rationale for shifting resources intended for CHA residents to other city agencies.

The argument goes like this: in view of the fact that public housing tenants are citizens of the city, resident services developed over the years by the CHA are duplicative and should be eliminated. (The counter-argument is that these services were an adaptive response to the failure of various city agencies to serve public housing residents.) Acting on this rationale, the CHA in the first phase of the “Plan for Transformation” dismantled resident services, including the CHA police force. This was promoted as cost-cutting and elimination of waste. It can also be seen as a reallocation of federal resources intended for public housing residents to other city agencies. CHA funds were shifted on a massive scale to the Chicago Department of Human Services, the Chicago Department of Aging, the Chicago Park District, and the Chicago Police Department. This pattern has led resident leaders such as Francine Washington, president of the Stateway Gardens resident council, to ask, "If we're citizens of the city, why is it necessary to take money out of the CHA budget and give it to other city agencies to get them to give us services?"

In the area of public safety, the CHA by the end of 2003 will have transferred $49.6 million to the Chicago Police Department. As of the end of 2002, $36 million had been transferred. An additional $13,600,000 for 2003 was approved by the Board of Commissioners at its November 19 meeting.

How does the CHA justify this massive transfer of resources to another city agency already obligated to provide services to public housing residents? Soon after the city launched "The Plan for Transformation" in 1999, it summarily disbanded the 270-member CHA police force. At that time, city officials reassured CHA residents that the Chicago Police Department (CPD) had adequate resources to provide full police services to public housing communities. They said that the Department had a $30 million federal grant that would be used to hire 375 officers to work in public housing. The $49.6 million transferred from the CHA budget to the CPD is above and beyond this $30 million grant. One can imagine the City arguing that additional funding has been required to address the consequences of the history of abandonment of public housing communities and to implement a transition to a new regime of respectful, competent law enforcement. But it does not make that argument, for this is a history and a need it is reluctant to acknowledge. Rather, the CHA stated in the resolution presented to the Board of Commissioners on November 19 that the $49.6 million given to the Chicago Police Department is intended to secure “supplemental police services, which are defined as over and above the baseline police services provided to residents of the City of Chicago.”

The resolution notes various services covered by these funds: "a customized policing plan for the Authority"; "enhancement of the Public Housing Section of the CPD"; "increased vertical foot and car patrol teams"; and "concerted patrol efforts within targeted developments." It also notes the need for additional manpower "to address concerns relating to relocation." But the basic logic is that these are supplementalservices provided in addition to the police services public housing residents receive as citizens of the city.

That this is the official stance of the CHA is demonstrated by a statement that appears in its response to Report No. 3 of the independent monitor of the relocation process, Thomas Sullivan. Addressing concerns raised by Mr. Sullivan about the dangers posed to residents by gang activity in the buildings in which they live and to which they are being relocated, the CHA writes:

CHA has provided a higher level of security for CHA residents than any citizen of Chicago receives through the Chicago Police Department.

This is not a misstatement blurted out in a moment of confusion or rhetorical panic. It is the considered statement of senior CHA officials. Mr. Sullivan comments:

This statement—which describes a condition of affairs dramatically different from what I have observed and learned—is especially troubling because it is included in an official, formal CHA document, presumably written after thoughtful consideration; the CHA response was sent to me more than three weeks after Report No. 3 was issued.

Having in mind the facts as I found them, and their ready availability, it seems not amiss to wonder who wrote the incredible sentence quoted above from the CHA’s response to Report No. 3, and who reviewed and approved it before it was sent to me.

What are the realities of policing in public housing? What do the “supplemental police services,” paid for out of the CHA budget, look like on the ground? What are the public safety needs of public housing communities and how might they best be met? What is the proper role of law enforcement as these communities are "transformed" into mixed income developments?

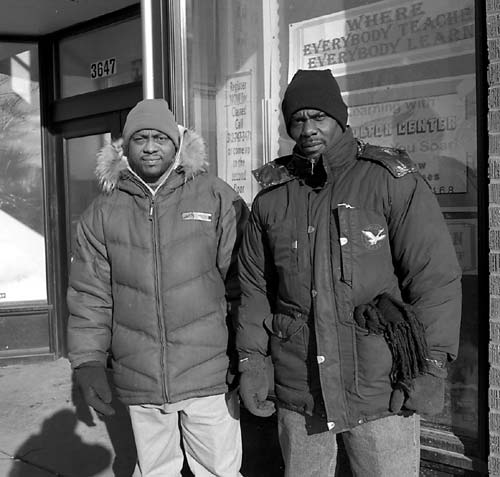

In a forthcoming series of articles, The View will report on the policing of public housing as we have observed it at Stateway Gardens. It is unlikely that the patterns of police conduct—and misconduct—described in this series are unique to Stateway. Presumably, similar patterns can be observed in public housing developments and other abandoned communities throughout the city. If anything, one might expect fewer flagrant abuses at Stateway, in view of the fact that it is located two blocks away from the administration headquarters of the Chicago Police Department.