Kicking the Pigeon

“Kicking the Pigeon” is a series of seventeen articles by Jamie Kalven published between July 6, 2005 and February 16, 2006 on The View From The Ground. It describes the incidents and underlying conditions that gave rise to Bond V. Utreras, a federal civil rights case that has figured centrally in the public conversation about police accountability in Chicago. The articles are presented below in the sequence in which they appeared.

April 13, 2003

On Sunday, April 13, 2003, at about 5:00 p.m., Diane Bond, a 48 year-old mother of three, stepped out of her eighth floor apartment in 3651 South Federal, the last remaining high-rise at the Stateway Gardens public housing development, and encountered three white men. Although not in uniform, they were immediately recognizable by their postures, body language, and bulletproof vests as police officers. Bond gave me the following account of what happened next.

“Where do you live at?” one of the officers asked. He had a round face and closely cropped hair. Bond later identified him as Christ Savickas.

"Right there," she pointed to her door.

He put his gun to her right temple and snatched her keys from her hand.

Keeping his gun pressed to Bond's head, he opened her front door and forced her into her home. The other officers followed. As Bond stood looking on, they began throwing her belongings around. When she protested, one of them handcuffed her wrists behind her back and ordered her to sit on the floor in the hallway of the two-bedroom apartment.

An officer with salt-and-pepper hair, whom Bond later identified as Robert Stegmiller, entered the apartment with a middle-aged man in handcuffs and called out to his partners, “We’ve got another one.”

Bond’s 19 year-old son Willie Murphy and a friend, Demetrius Miller, were playing video games in his bedroom at the back of the apartment. Two officers entered the room with their guns drawn. They ordered the boys to lie face down on the floor, kicked them, handcuffed them, then stood them up and hit them a few times.

“Why are you’all doing this?” Bond protested.

Savickas came into the hall and yelled at her, “Shut up, cunt.” He slapped her across the face, then kicked her in the ribs.

In the course of searching the apartment, the officers threw Bond’s belongings on the floor, breaking her drinking glasses. Savickas knocked to the floor a large picture of a brown-skinned Jesus that sits atop a standing lamp in a corner of the living room.

“Would you pick up my Jesus picture?” Bond appealed to him.

“Fuck Jesus,” replied Christ Savickas, “and you too, you cunt bitch.”

Stegmiller then forced Bond to her feet, led her into her bedroom, and closed the door.

“Give us something to go on,” he told her. “If you don’t, we’ll put two bags on you.” He took off his bulletproof vest and laid it on the window sill. He removed the handcuffs from her wrists.

“Look into my eyes, and tell me where the drugs are. If you do,” he gestured toward the hallway where the man he had brought into the apartment was being held, “only that fat motherfucker will go to jail.”

Another officer entered the bedroom. Bond later identified him as Edwin Utreras. “Has she been searched?” he asked. “I’m not waiting on no female.”

Utreras took her into the bathroom and closed the door. He ordered her to unfasten her bra and shake it up and down. Sobbing, she did as he told her. He ordered her to take her shoes off. Then he told her to pull her pants down and stick her hand inside her panties. Standing inches away in the small bathroom, he made her repeatedly pull her panties away from her body, exposing herself, while he looked on.

“You’ve got three seconds to tell me where they hide it or you’re going to jail.” She extended her arms, wrists together, for him to handcuff her and take her to jail.

Utreras didn’t handcuff her. He returned her to the hall and ordered her to sit on the floor. An officer she later identified as Andrew Schoeff was beating the middle-aged man Stegmiller had earlier brought into the apartment. Bond and the boys looked on, as he repeatedly punched the man in the face.

“He was beating hard on him,” recalled Demetrius Miller. “Full force.”

Knocked off balance by his blows, the man fell on a framed picture of the Last Supper that was resting on the sofa. The glass shattered.

“There ain’t nothing in this house,” Bond kept insisting. “There ain’t nothing in this house.”

“Give us the shit, and we’ll put it on him,” said Stegmiller.

The name of the man to whom he referred, the man his colleague was beating, is Mike Fuller. On Fuller’s account, he had been descending from a friend’s apartment on the sixteenth floor, when he encountered Stegmiller coming up the stairs between the fifth and sixth floors.

“Where are you coming from?” Stegmiller demanded.

“From the sixteenth floor,” he replied.

“You’re lying,” said Stegmiller. “You’re coming from the eighth floor.”

He grabbed Fuller and searched him. Finding $100, Stegmiller pocketed it, then pushed him up the stairs. “I wouldn’t mind shooting me a motherfucker,” he said, “if you try to run.”

Stegmiller took Fuller to Bond’s apartment. “He kept telling me that’s where I’d run to,” said Fuller. Once inside the apartment, Stegmiller took a flashlight from a shelf in the kitchen and beat the handcuffed Fuller on the head with it. (“They don’t beat you,” he observed, “till after they cuff you.”) “If I find dope,” Stegmiller threatened, “it’s gonna be yours.”

“I saw how they ramshackled her house,” Fuller recalled.

The officers, having found no drugs, were now drifting out of the apartment. Stegmiller made a proposition to the two boys: if they beat up Fuller, they could go free. “If you don’t beat his ass,” he told Willie, “we’ll take you and your mother to jail.”

The boys put on a show for the officers. (“Hitting him on the arms, fake kicking,” Miller said later. “No head shots.”) After they threw a few punches, Stegmiller intervened and removed Fuller’s handcuffs “to make it a fair fight.” The three rolled around on the floor for a couple of minutes. The officers looked on and laughed.

“I told the boys to make it look good,” Fuller recalled. “It was for their amusement.”

Stegmiller applauded. He left laughing. No arrests were made.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, April 14, 2003, and continuing to the present; interviews with Willie Murphy, Demetrius Miller, and Michael Fuller; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al, a federal civil rights suit brought by Ms. Bond.

Officers Robert Stegmiller, Christ Savickas, Andrew Schoeff, and Edwin Utreras deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

The Setting

Stateway Gardens, the community where Diane Bond has lived for the last twenty-seven years, is one of the high-rise public housing developments being redeveloped by the Chicago Housing Authority as part of its “Plan for Transformation.” Bounded by 35th and 39th Streets and State and Federal Streets, Stateway originally consisted of six seventeen-story and two ten-story high-rises on 33 acres. It provided 1,644 units of family housing. Under the redevelopment plan, private developers will build a “mixed income community” consisting of 1,315 units of housing, 439 of which will go to public housing residents. This “new community” will be called Park Boulevard.

The Stateway numbers—a net loss of 73% of the original public housing units—reflect the essential trajectory of the Plan for Transformation. City officials and developers speak of this massive reallocation of public resources to private hands in highly moralistic terms. Public housing developments, Mayor Daley has remarked more than once, lack “soul.” The new communities to be built on the land cleared by demolition will, so the logic goes, restore the soul of the city.

In a display that was part of an exhibition on the Plan for Transformation at the Chicago Historical Society last year—more an exercise in public relations for the CHA than historical inquiry—Stateway Gardens was described as "isolated." This characterization is consistent with the prevailing social scientific discourse on urban poverty. It is not, however, consistent with geography. It would be more accurate to say that Stateway, like most of the CHA archipelago, is not isolated but abandoned. Now that the rest of the Stateway buildings have been razed, Diane Bond looks out from her eighth-floor apartment, over the Bridgeport neighborhood and the Illinois Institute of Technology campus, at the downtown skyline. To the west, on the other side of the Dan Ryan Expressway, she can see White Sox Park. To the east, she can see De La Salle High School where both Mayor Daleys went to school. And just out of sight, blocked from view by the eastern tier of her building, located three blocks away at 35th and Michigan, is the administrative headquarters of the Chicago Police Department. As I have observed elsewhere, the question posed by this landscape is: who has isolated themselves from whom?

* * * *

“It’s like a nightmare,” Bond told me the day after her encounter with the police. “All I did last night was cry.”

When I knocked on her door, she was cleaning up. She gave me a tour and showed me the damage—the shattered picture of the Last Supper, the damaged frame of Willie’s high school graduation picture, the broken drinking glasses, the clothes and objects strewn around Willie’s room, the one room she had not yet cleaned up.

I had at that time known Diane Bond for several years. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I worked out of an office on the ground floor of 3544 S. State, the building in which she lived. Every so often I would see her in passing, most often going to or coming from her job as a public school janitor. I didn’t know her well but formed an impression of a cheerful woman in coveralls who moved through the turbulent scene “up under the building”—at once drug marketplace and village square—with an easygoing, friendly manner.

In September of 2002, 3544 S. State was closed in preparation for demolition. Residents were given the choice of taking a housing voucher and moving into the private housing market or remaining on site. Bond opted to move to 3651 S. Federal. When the day came, the CHA provided moving vans for Bond and other residents relocating on site. At the end of the day, I encountered her, in a characteristically ebullient mood, ferrying the last of her possessions across the development in a shopping cart.

Her apartment in 3651 S. Federal is deeply inhabited. Two large, comfortable sofas, arrayed around a coffee table, dominate the living room. The top of the television cabinet functions as a sort of household altar for religious objects and family photos, among them pictures of her three sons: Delfonzo, now 30 years old, Larry, 29, and Willie, 21. Working as a janitor, Bond raised her boys as a single mother. She expresses pride in the fact that they have largely managed to stay clear of trouble in an environment where that is no small achievement. For the last three years, she has been involved with a man named Billie Johnson. Quiet and gentle in manner, Johnson labors in the economy of hustle—repairing cars, helping maintain the Stateway Park District field house and grounds, doing odd jobs for his neighbors.

* * * *

At my urging, Bond went to the Office of Professional Standards (OPS) of the Chicago Police Department to register a complaint against the officers who she said had assaulted her. As it happens, the OPS office is located at 35th and State in the IIT Research Institute Tower, the 19-story building visible from her apartment that stands like a wall of glass and steel between Stateway and the IIT campus to the north.

OPS investigates complaints of excessive force by the police. It is staffed by civilians and headed by a chief administrator who reports to the superintendent of police. When someone makes a complaint to OPS, an investigator takes down his or her statement of what happened. The individual is asked to review the statement and to sign it. In theory, OPS conducts its own investigation, interviewing the police officer(s) involved and any witnesses, then renders a judgment. In the vast majority of cases, it finds that the complaint is “not sustained”—i.e., the investigators could not determine the validity of the allegations of abuse. In a small number of cases each year, OPS sustains the complaint and recommends discipline for the officer(s) involved. An officer facing discipline may appeal to the Police Board, a body composed of nine civilians appointed by the mayor. The board has the power to reduce the punishment recommended by OPS or the superintendent and to reverse OPS altogether.

OPS has long been sharply criticized by human rights activists who argue that it functions not as a vehicle for holding the police accountable but as a shield against such accountability. They cite the numbers. For example, from 2001 through 2003, OPS received at least 7,610 complaints of police brutality. Significant discipline was imposed by the CPD in only 13 of those cases—six officers were terminated and seven were suspended for 30 days or more. In other words, an officer charged with brutality during 2001 – 2003 had less than a one-in-a-thousand chance of being fired.

It is, thus, extremely unlikely that an OPS investigation will yield any meaningful discipline for the officers involved. Yet it does not seem unreasonable to hope that a pending OPS investigation will at least serve to deter the officers named from further contact with the person who filed the complaint. That, at any rate, is what I told Diane Bond by way of reassurance.

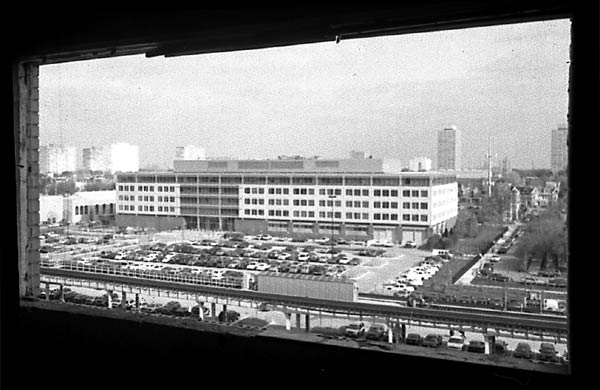

3542-44 S. State Street being demolished with police headquarters in the background

April 28, 2003

On the evening of April 28, 2003—two weeks after she filed a complaint with OPS about the April 13 incident—Diane Bond returned home at about 7:30 p.m. from the corner store. She encountered Officers Stegmiller, Savickas, Utreras, and Schoeff outside her apartment door. Also present was a fifth officer she later identified as Joseph Seinitz. He was tall and lean, in his thirties, with closely cropped blond hair. She recognized him as the officer known on the street as “Macintosh.”

The officers had two young men in custody. Demetrius Miller was one of them; she didn’t recognize the other. His name, she gathered, was Robert Travis. Bond recounted the incident to me the next day.

One of the officers barked at her, “Get the hell out of here!” Moments later, as she was descending the stairs, another yelled, “Come here!” Seinitz came down the stairs and grabbed her. Holding her by the collar of her jacket, he dragged her back up to the eighth floor, her body scraping against the stairs.

While Seinitz held Bond, Savickas punched her in the face and demanded, “Give me your fucking keys!”

“They snatched my jacket off and took the keys out of my pocket,” she told me. “I was so scared, I pissed on myself.”

The officers entered her apartment. They ordered her to sit on the sofa in her living room. The two young men, handcuffed, sat on her glass coffee table.

Stegmiller came in from outside the apartment and placed two bags of drugs on the top of her microwave. (He would later testify that he had found the drugs in an “EXIT” sign in the corridor outside her apartment.)

One officer stayed with Bond and the two boys, while the other three searched the apartment. The officer leaned back on her television cabinet where family pictures and religious artifacts were arrayed. She begged him not to sit on her icon of the Virgin Mary.

“Fuck the Virgin Mary,” he said, as he swept his hand across the top of the cabinet, knocking the Virgin Mary and other religious objects to the floor.

Seinitz and two other officer were searching Bond’s bedroom. They motioned to her to come into the room. They told her to pull down her pants. Then they told her to pull down her panties.

Seinitz brandished a pair of needle-nosed vise-grips and threatened to pull out her teeth if she didn’t cooperate.

“Why’d you pee on yourself?” one of them taunted.

They ordered her to bend over with her back to them, exposing herself. While she was in that position, they instructed her to reach inside her vagina "and pull out the drugs."

Bond was overcome by terror. As a child and young woman, she had, she told me, suffered repeated sexual abuse at the hands of men, including a gang rape when she was a high school student. Now, despite the official complaint she had made against these officers, they were again swarming around her, threatening her, cursing her, forcing her to undress. She feared they would rape or kill her. "I didn't know what they were going to do next." She only knew that each thing they did was worse than the last.

They brought her back into the living room. One of the officers instructed Travis to “stiffen up,” as he punched him repeatedly in the stomach.

“Do you want us to put a package on her?” the officer asked Travis.

“I don’t care what you do with her,” he replied.

They left with the two men.

Bond locked the door, collapsed on her sofa, and wept.

* * * *

A neighbor, Barbara White, who lives on the second floor of 3651 S. Federal, reported she too was assaulted that night by the same group of officers after they left Bond’s apartment.

White was employed at that time as a security guard. “I’ve lived here twenty-two years,” she told me, “and never had any problems.”

According to White, a friend named Bruce Reed came by at about 8:15 p.m. to see if she wanted anything from the store. When Reed came to the door, she was in the kitchen washing dishes. She said no. When he turned to leave, five police officers were at the door.

“What’s wrong?” White asked.

“You put my fuckin’ life in danger,” said one of the officers. White’s description of him—white, salt-and-pepper hair, about 40 years old—fits Stegmiller. She recognized him as one of the officers who some months earlier had demanded, in the course of searching her 16-year-old goddaughter, that the girl expose her breasts.

Stegmiller claimed White had yelled out the warning “Clean up!” when the police first arrived at the building earlier that evening. She denied she had done so. He slapped her across the face.

“You slap her,” he ordered Reed.

Reed refused. “I’m not gonna slap her.”

“If you don’t slap her, you’re going to jail.”

“You might as well take me to jail, ‘cause I’m not gonna put my hand on her.”

White tried to get to the telephone to call 911. Stegmiller blocked her path and threatened her, “Bitch, if you call 911, I’ll come back and fuck you up myself.”

The officers left. White called 911 and requested an ambulance which took her to Michael Reese Hospital. She was examined, then took the bus home.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, April 29, 2003, and continuing to the present; interviews with Demetrius Miller, Barbara White, and Bruce Reed; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officers Robert Stegmiller, Joseph Seinitz, Christ Savickas, Andrew Schoeff, and Edwin Utreras deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

Old Wounds

Being forced to expose herself while Officer Seinitz and the others threatened her was “like a dry rape,” Diane Bond told me the day after the April 28 incident. She mentioned then that she had suffered violence at the hands of men when she was a girl. Later she told me the full story.

It has been my fate as a man and as a journalist to hear many such stories. Inevitably, I feel a tension between my hunger for the details—details that may obscure more than they reveal—and the desire to cover my ears. I resist entering imaginatively into the experience of being rendered utterly powerless. Although I am acutely aware of this dynamic, I still must work to resist seizing on details that explain why the victim was raped. My impulse is not so much to blame the victim as it is to find a way to differentiate myself and those close to me from the suffering person before me.

As Diane Bond began to tell her story, I saw a familiar upwelling in her eyes—not tears but rather a sudden shift in emotional gravity.

She grew up on the West Side. Her natural father left when she was a small child. Her mother remarried. Diane was six years old at the time. From the start, her stepfather abused her. As a little girl, she had long hair. He would take her into the bathroom, ostensibly to comb her hair, sit her up on the washbasin, and fondle her. He told her that if she ever said anything, her mother would go to jail and she would never see her again.

Silenced by his threats, she didn’t say anything, until one day her mother caught her and her brother pretending to smoke cigarette butts they had fished out of an ashtray.

“I’ll have your stepfather whup you,” she told the children.

“No, Mama,” Diane blurted out, “he did the pussy to me.”

Her mother didn’t believe her. “He told my mother that I was messing with him, and she believed him.”

As Bond grew up, her stepfather continued to prey on her. When she was a teenager, he would try to spy on her as she undressed. One night when she was thirteen, he came into her bedroom in his under shorts in the middle of the night. She looked up, saw him looking down at her, and screamed. Her mother put him out that night, but he soon came back.

In July, 1972, when Bond was 17 years old, she had argument with her mother. The family was living in Englewood at the time. It was about 10:30 or 11:00 at night. She can’t remember what the argument was about. “My mother was strict. It may have been because I came home late.” Upset, she ran out of the house. She was barefoot, wearing only shorts and a blouse. At 60th and Halsted, three men grabbed her. They took her to an abandoned building. One ripped her blouse off. Another kicked her between the legs. The third raped her repeatedly. They held her from 12:00 to 5:00 a.m. When they released her, she sat dazed and disoriented on a bench at 63rd and Halsted. A woman driver stopped and gave her a ride home. Her mother immediately called the police.

Bond remembers sitting on the sofa and talking with the police. They were, she said, “kind” toward her. She felt weirdly displaced. “It was as if I wasn’t there. Everything seemed very far away.”

The police apprehended the three men, and she brought charges against them.

That fall she returned to Crane High School. One day in September during lunch break she was outside the school. The boyfriend of her best friend Gail, known on the street as Son, told her that Gail, who had recently had a baby, wanted to see her. She was, he said, upstairs in an apartment in a nearby building. Diane noticed a group of teenage boys hanging out on the corner across the street.

“They’re not coming, are they?”

Son assured her they were not.

He led her upstairs into the apartment. The boys she had seen on the corner entered the apartment via the backdoor. There were five in all, including Son. She screamed. They held her down and took turns. The first to rape her was Son.

When they released her, she made her way back to school. She went to the principal and told him what had happened. He called the police. She was taken to Presbyterian St. Luke’s Hospital. The police brought one of the boys to the hospital, and she identified him. They then drove her around the area, and she identified the other four on the street. They were arrested and charged.

When the case came to trial, according to Bond, “the mothers lied for their sons” to provide them with alibis. The defendants were acquitted.

Bond’s mother told her that as she left the courtroom, she heard a man say, “If I was them, I wouldn’t have let her go. I’d have blown her brains out.”

The case arising out of the July rape was still in progress. Demoralized by the outcome of the September case, Bond didn’t go back to court. She dropped the case.

“Is it hard for you to talk about this?” I asked.

“I’m not crying on the outside,” she replied, “but I’m crying on the inside.”

April 30, 2003

On April 30, 2003—two days after her second encounter with the police—Bond and her boyfriend Billie Johnson went downstairs at about 11:30 p.m. They were going to the store to get some wine. As they came out of the stairwell into the elevator corridor in the lobby, they encountered Officers Stegmiller and Savickas. Stegmiller grabbed Bond by the arm.

“Where are you going?” he demanded.

“To the store.”

She had her keys in her hand.

“Give me your keys,” he said. “Give me your goddamn keys.”

“I’m not going to give you my keys,” she protested. “I’m not going through that again.”

She shifted her keys from one hand to the other and put them in her pocket. Stegmiller grabbed her around the throat and pushed her up against the elevator door.

“I’ll beat your motherfucking ass.”

“Somebody please help me,” she called out. “Please help me.”

Savickas stood by, while Stegmiller choked Bond. When Johnson appealed to him to intervene, Savickas gave him a hard push in the chest.

Only when other residents came on the scene did Stegmiller release Bond and tell her, “Get the fuck out of here.”

“I was crying, I was angry. I was hysterical,” Bond recalled. “I told my old man, ‘I’m so tired. I’m tired of this.’”

She and Johnson went directly to the Office of Professional Standards in the IIT building at 35th and State. Although OPS is open 24 hours a day, security personnel in the lobby of the building would not let her go up to the office. She left and went to the administrative headquarters of the Chicago Police Department at 35th and Michigan. The officers at the desk were not welcoming. They threatened to put Bond and Johnson in lockup. In the end, they took down her name and address. She then went to a store on the corner of 37th and State and attempted to call OPS, but the phone in the store was dead.

It was raining hard. Bond and Johnson returned to the building. The police were still there. They slipped in. He went to her apartment on the eighth floor. She went upstairs to thank the neighbors whose presence had stopped Stegmiller’s assault on her. In a vacant apartment on the fifteenth floor, she saw Seinitz—“Macintosh.” He didn’t see her. She fled the building. Again, she attempted to go to OPS, and again she was barred by security. She returned to 3651-53 South Federal and waited outside in the rain and darkness for about half an hour until the police left the building. Then she climbed the stairs to her home.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, May 1, 2003, and continuing to the present; an interview with Billie Johnson; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officers Robert Stegmiller and Christ Savickas deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

“Bridgeport”

Officers Seinitz, Savickas, Stegmiller, Utreras, and Schoeff were, until recently, familiar presences at Stateway Gardens and other South Side public housing developments. With the exception of Seinitz who is known as "Macintosh," they are referred to on the street not by their names but as "the skullcap crew" (they often wear watch caps) or "the skinhead crew" (several have buzz cuts). They are reputed to prey on the drug trade--routinely extorting money, drugs, and guns from drug dealers--in the guise of combating it. But what distinguishes them, above all, say residents, is their racism. Several are rumored to have swastika tattoos on their bodies. One resident described them to me as "KKK under blue-and-white." And black officers have been heard to refer to them as "that Aryan crew." "They get their jollies humiliating black folks," a former Stateway resident told me. "They get off on it."

Diane Bond, in the aftermath of her encounters with the crew, seemed stunned by the ferocity of their racism. “Me, I don’t see no color, but they’re prejudiced,” she observed. “I hear they’re from Bridgeport.”

The officers were in fact assigned at the time to the Public Housing South unit of the Chicago Police Department. Until it was disbanded in the fall of 2004, Public Housing South operated out of offices at 38th and Cottage Grove in the Ida B. Wells development. The rumor that they were “from Bridgeport” was telling. For Stateway residents, “Bridgeport” carries a heavy freight of meanings and associations. It refers to the traditional seat of political power in the city. It evokes an intimate landscape containing great distances: Bridgeport is just across the Dan Ryan Expressway but a world away. And it recalls a bitter history of racial violence that includes among its defining events the 1919 riots when 4,000 blacks massed at 35th and State to defend their neighborhood against marauding white gangs, and the cruel 1997 beating that left Lenard Clark, a 13-year-old Stateway boy who had ventured into Bridgeport on his bicycle, brain damaged.

There is knowledge on the street about the skullcap crew; it resides in people's nerve endings; it flows readily between those who share a body of experience and a common language. The Bridgeport rumor reflects an effort to make sense of that knowledge by constructing a context around it. It's an effort to place the crew. Such attempts at explanation can give rise to rumors and, at least in the case of "Macintosh," to urban myths. (Last year when he was not seen at Stateway for several weeks, competing rumors circulated to explain his absence: he had been arrested in a federal sting operation; he had left the police force to become a bounty hunter; and he had gone to Iraq to fight as a mercenary.) Yet the challenge presented by the knowledge of the street remains.

As a reporter, I confront a similar challenge: to place the skullcap crew within broader contexts that help explain what at first seems inexplicable. Assume for the moment that Diane Bond's account is true. What possible rationale could there be for members of the skullcap crew to repeatedly invade her home and her body? These incidents have come to public attention because of the circumstance--highly unusual in the setting of public housing--that Bond has relationships that enabled her to get skilled lawyers to take her case. It should not be assumed because the incidents have come to light that they are the worst crimes the crew committed during the years they worked in South Side public housing communities. They may not even be the worst crimes they committed on the dates in question.

Against this background and making these assumptions, we will explore the multiple contexts that frame the Diane Bond story. Those contexts include "the war on drugs" as waged in Chicago public housing, the CHA's Plan for Transformation, and the policies and practices of the CPD with respect to complaints of police misconduct. At the center of this narrative inquiry is the question: if a group of rogue police officers operated for years in Chicago public housing with impunity, what conditions would be required to make possible their criminal careers?

“Up Under the Building”

Drug dealers' place of work "up under" a building at Stateway Gardens.

The alleged abuses of the skullcap crew were committed in the context of what we have become accustomed to calling "the war on drugs." In view of the extent of drug use and hence distribution throughout American society, this is a strange war in that it is waged on some fronts and not others. After noting that there are five times more white drug users in the United States than black, a report issued in 2000 by Human Rights Watch states:

Blacks constitute 62.6 percent of all drug offenders admitted to state prisons in 1996, whereas whites constitute 36.7 percent. In certain states, the racial disproportion among drug admissions are far worse. In Maryland and Illinois, blacks constitute an astonishing 90 percent of all drug admissions.

— Human Rights Watch, "Punishment and Prejudice: Racial Disparities in the War on Drugs," A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 12, no. 2, May 2000.

Blacks make up 15.1 percent of the population of Illinois and 90 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. What proportion of that 90 percent were arrested in Chicago? What proportion were arrested in abandoned communities such as Stateway Gardens? I raise these questions in order to suggest a perspective from which the "war on drugs" looks more like a war being waged against certain communities: the drug trade persists, while the communities are devastated.

The statistics on racial disparities in the drug war are stunning. Yet they do not fully convey the futility and absurdity of that war as it plays out from day to day in communities such as Stateway Gardens. For that, one needs a sense of what the war looks like on the ground.

* * * *

Until recently, the primary visible economic activity at Stateway, conducted openly, in the shadow of the headquarters of the Chicago Police Department, was the drug trade. An endless parade of customers passed through the drug markets in the open-air lobbies of the Stateway high-rises. Black and white, well-heeled and down-and-out, they came to buy “rock” (crack) and “blow” (heroin) from the young men in the drug trade. At various locations around the perimeters of the buildings, solitary figures stood watch for 12-hour shifts “doing security.” Most were older men and women. Almost all were drug users who supported their habits by doing this work. Like street criers, they sang out the brand names of the drugs sold in the particular building. “Dog Face!” “Titanic!” “FUBU!” And they acted as lookouts. If they saw a police car approaching, they called out a warning—“blue-and-white northbound on Federal”—and the message was relayed from voice to voice into the interior shadows of the drug bazaar. [See “Fred Hale” for an extended interview with a former drug dealer who vividly evokes his life and work “up under the building.”]

Coming and going to their homes, residents passed through this marketplace. Day after day, they saw the same drug dealers in the same positions conducting their business in the open. Why, they asked in every available forum, can’t the police shut the drug trade down? Are the bored young men loitering in the lobbies such master criminals? Is the security system of drug addicts shouting out warnings so effective the police are unable to penetrate it? Community members don’t have the moral luxury of demonizing the young men dealing drugs. They see the sweatshop conditions in which they work. They have watched many of them grow up and drift—for lack of a job or the imagination to envision an alternative—into the drug trade. They know them in other roles besides “gangbanger”: as son or nephew, as boyfriend or teammate, as neighbor, as friend. Francine Washington, president of the resident council at Stateway, elegantly encapsulates such knowledge in the phrase “our in-laws and our outlaws.”

This orientation does not excuse criminal activity. On the contrary, desperate for some sort of relief, residents will sometimes support constitutionally suspect measures—sweeps, gang loitering ordinances, one-strike eviction policies, etc.—even at the cost of their own freedoms. They just want to see something done. From their perspective, the “war on drugs,” as waged in public housing, is at once ineffectual and abusive. The police hit the building, and the drug dealers fall back. Having knocked some heads and perhaps made some arrests, the police leave, and the dealers return. A great many arrests are made over time, but rarely do the police take into custody the major players in a given building. This ongoing exercise in futility is occasionally punctuated by police shows of force—for example, after (though not during) an outbreak of shooting between gang factions—that take the form of large numbers of officers sweeping through a building like an invading army and indiscriminately treating everyone living there as presumptively guilty of drug dealing and gangbanging.

Residents make fine distinctions among the different types of police abuse that occur under the cover of “the war on drugs.” A certain degree of excessive force is routine. For some officers, brutality is sport. They grade each other on the blows they inflict. (“That was a good one.”) Then there is the racial invective—“niggers,” “monkeys,” “hood rats,” etc.—almost invariably laced with the language of gender violence. Such words are not simply uttered under the breath; one sometimes hears them over the PA systems of police vehicles. According to residents, the practice of planting drugs is widespread; it is clearly widely feared. Above all, one hears stories of street level corruption. An African-American gang tactical officer described it to me this way: “Think of the police as the working poor. Create a situation in which there’s lots of money and drugs on the street in neighborhoods no one gives a fuck about. What do you think is going to happen?” Francine Washington jokes that the drug markets up under the buildings are “the policeman’s ATM machine—where they can go when they need to pay their mortgage or car note.” The corruption takes various forms. An arrest is made, but not all the drugs and money seized make it back to the police station. Alternatively, no arrest is made, but money and drugs are seized. (“Think of it as bail money,” a victim of this practice reported an officer saying. Another described an officer exulting after taking a large wad of cash off a drug dealer, “This year my kids are going toDisneyland!”) Then there is outright extortion—officers who demand pay-offs from drug dealers as the price of not raiding the buildings they control. At the other extreme is the practice, as one resident put it, of taking “little money” as well as “big money.” Some officers don't distinguish between drug money and grocery money. They take any cash they find in the pockets and homes of the poorest residents of the city. For years, friends at Stateway have told me that certain officers could be counted on to show up at the development on the first and fifteenth of the month—on check day.

Conditions of abandonment, in the shadow of the police headquarters, have allowed space for criminal activity by both drug dealers and police officers. The numbers of either type of criminal need not be large to have a devastating effect, for fear is a powerful magnifier. The image of the gangbanger/drug dealer looms large in the imaginations of many of us who live outside public housing, eclipsing the rest of life in communities such as Stateway. Similarly, a relatively small number of rogue police officers, if allowed to operate with impunity, can become the cruel and corrupt face of civil authority for an entire community.

The CHA Plan and Public Safety

The launching of the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation in 1999 promised an end to the abandonment and exploitation of CHA communities. Terry Peterson, the CEO of the CHA, is eloquent on the theme that public housing residents are citizens of Chicago with equal claims to its services. Among the first things the City did after launching the Plan was to disband the 270-member CHA police force. The policing of public housing was shifted to the Chicago Police Department, which created a public housing unit and, drawing on a $30 million federal grant for the purpose, hired additional officers to staff it.

The attractive principle that CHA residents are full citizens of the City turned out in practice to be less a new standard of care and accountability than a rationale for shifting federal resources intended for public housing residents to other city agencies, such as the Department of Human Services, the Park District, and the Department of Aging, as well as the CPD. By the end of 2004, the CHA had transferred more than $60 million from its budget to the CPD. (If one adds CHA funds given to the CPD specifically for the Cabrini-Green and Henry Horner developments, the total comes to more than $70 million.) One can imagine arguing that this transfer of funds was required to facilitate a transition to a new regime of respectful, sustained law enforcement. That is not, however, the argument the CHA made. Rather, it stated in a resolution presented to its Board of Commissioners that the funds were being transferred to the CPD for the purpose of securing “supplemental police services, which are defined as over and above the baseline police services provided to residents of the City of Chicago.”

The CHA reiterated its stance on public safety for its tenants in a 2003 exchange with Thomas Sullivan, the former U. S. Attorney who served as the independent monitor of the relocation process during 2002-2004. In one of his reports, Sullivan had expressed concerns about unchecked gang activity in buildings undergoing relocation and in buildings to which families were being relocated. The housing authority stated in its reply:

CHA has provided a higher level of security for CHA residents than any citizen of Chicago receives through the Chicago Police Department.

It’s hard to know how to characterize this statement. Sullivan called it “incredible.”

Over a period of five years, I witnessed the entire relocation process at Stateway. I frequently visited each building as it went through relocation; and I lived through the process on a daily basis in the building where my office was located. There is no reason to assume conditions at Stateway—relative to other developments undergoing relocation—were uniquely bad. On the contrary, one might expect them to be somewhat better, if only for public relations reasons, in view of the proximity of the police headquarters two blocks away

Yet at no point during these years was effective, respectful policing provided on a sustained basis. The reality at Stateway—and, I assume, at other communities being “transformed”—is that, as the onsite community contracted to six buildings, then to four, then to two, and ultimately to one, the quality of policing did not significantly improve. In their final months, the Stateway buildings descended into purgatorial conditions exploited by both the drug trade and by police officers parasitic on it.

That is not to say that the policing of Stateway has not been better at some times than others. For some months last year and early this year, in response to complaints from the resident council, there was an around-the-clock police presence at 3651-53 S. Federal, the one surviving high-rise. It took the form of a squad car parked in proximity to the building. The officers rarely got out of the car, but at least they performed a scarecrow function sufficient to deter open drug dealing. In recent months, the police presence has been intermittent, and drug dealers have been drifting back into the building.

Whatever the fluctuations in police presence over time in response to crises and public pressure, there has been no evidence of a plan or strategy to provide minimally adequate law enforcement to public housing communities on a sustained basis. Just as the City did not maintain the buildings in the expectation they would soon be demolished, so it did not invest in nurturing the relationships necessary to effective law enforcement. After all, what does "community policing" mean in the case of a community in the process of being dismantled?

In retrospect, it is clear that CHA’s public safety plan for these communities has been their erasure. Such is the logic of abandonment: conditions that should be the basis for calling public institutions to account are invoked by those very institutions in support of their agendas. Thus, the CHA’s failure to maintain the high-rises becomes the rationale for their demolition. And the CPD’s failure to provide adequate law enforcement in public housing communities becomes the rationale for obliterating those communities and starting over. This logic helped create the space through which, according to residents, the skullcap crew moved, living off the land and abusing community members at will, in the last years of high-rise public housing.

March 29 and 30, 2004

A question persists at the center of this narrative. Why? Assuming Diane Bond's account is true, why did members of the skullcap crew repeatedly invade her home and her body? What possible rationale could there be for their conduct? The abuses occurred in the context of the "war on drugs." That was the pretext for raiding her building, searching her home and person, and interrogating her. But does the enforcement of drug laws, in the absence of individualized suspicion (much less a search warrant supported by probable cause), explain the abuses? Does it make sense of the senseless, sadistic conduct alleged? This is not an easy question to answer. For it demands we entertain the possibility that the abuses were an end in themselves and the drug war a vehicle to that end: the possibility that members of the Chicago Police Department terrorized Diane Bond for the perverse pleasure of it.

I recall arriving at 3651 South Federal on a winter day in 2003, just as an unmarked police car was driving away. Once it was out of sight, the drug marketplace up under the building would reopen for business. Several people were standing outside the building, looking on. Among them was a woman known on the street as Betty Boop, who acts as a lookout for drug dealers to support her heroin addiction.

“You know what that crazy man did?” she asked me, referring to one of the officers. “He just walked up and kicked that bird for no reason.”

She pointed to a pigeon on the pavement. It was wobbly and disoriented—in obvious distress.

“Now why did he have to do that?” Betty asked.

The image comes back to me now, as I try to make sense of the patterns of the skullcap crew: kicking the pigeon. Casual cruelty can become a way of life in a setting where everything is permitted, where you enjoy de facto dominion over other human beings who are by definition not to be believed. Any account they might give as victims or witnesses is impeached in advance, for they are gangbangers and drug dealers. They are the mothers and grandmothers of gangbangers and drug dealers. They are residents of a public housing development that is seen less as a community than as a loose criminal conspiracy to engage in gangbanging and drug dealing. Some officers are made uncomfortable by the license this perverse logic confers upon them; they know if they don’t restrain themselves, nobody else will. And some exult in the power it gives them to toy with other human beings.

Seen in this light, it was not something threatening about Diane Bond that drew the skullcap crew to her. It was something vulnerable.

* * * *

In early March of 2004, ten months after her last encounter with the skullcap crew, I visited Bond in what is now the lone surviving building at Stateway Gardens. It stands at the center of thirty-three acres of vacant land. Waiting for her to answer the door, I was struck anew by how exposed her situation was: a woman alone on the eighth floor of a half-vacant high-rise in the middle of a desert of demolition. There was a hand-lettered sign affixed to the door:

Stop!!! Read Don’t Knock On my Door Unlest It For a Good Cause (Not Stupid)

The reason for the sign, she explained, was that the police had told her they would arrest her, if she let anyone they were after into her apartment.

I found Bond despondent. She was unemployed. She was broke. She had fallen behind on her rent. Her isolation had deepened because she could no longer afford a telephone. And her fear of the police seemed only to have intensified with the passage of time.

“I can’t stand," she said, "that I’m scared even to open my door.”

She spoke of the gang rape she suffered in high school with startled immediacy as if it had occurred recently rather than thirty years ago.

“All these years,” she said, “I’ve been holding it inside.”

As I listened to her talk about her sense of exposure and helplessness, I was reminded of an image a friend once used to describe how people “recover” from traumatic violence. It is, she said, akin to the way the body responds to tuberculosis. One does not get over TB by excising it or expelling it from the body; rather, the body walls off the bacteria and contains them. Similarly, the victim of terrorizing violence rebuilds her world, containing but not erasing the virulence that has entered her life. In this sense, a traumatic event changes the underlying terms of existence. It remains present within one’s nervous system and soul as a continuing vulnerability. Even when one has rebuilt one's life, the trauma may under certain circumstances be reawakened with the force and immediacy of the original assault. And so for Diane Bond, it appeared, her encounters with the skullcap crew had reopened the wounds of earlier violations. While the crew presumably wasn’t aware of her history of sexual violence, it’s not hard to imagine they had picked up the scent.

Finding Bond in despair, I could see more clearly how gallantly she had responded over time to the cruelties she had suffered as a young woman. As the structure of a building is revealed by the process of demolition, so the design of the life she had built for herself after violence was poignantly evident. She had invested herself in her work and her family. She had found solace in religion; prayer and counting her blessings were part of her daily routine. And she had been deeply embedded in her community, moving through it gracefully without evident fear, enjoying the passing encounters and conviviality of the street. It was these structures of meaning and security, this hard-won sense of being at home in the world, that were now collapsing.

* * * *

At about 11:30 p.m. on March 29, 2004, Bond was descending the stairs from her apartment. In the stairwell she encountered Officer Robert Stegmiller and another officer. Stegmiller had a screwdriver in his hand. He ordered Bond to come with him and threatened to stick her in the neck with the screwdriver if she didn’t comply. The two officers seized her, threw her to the ground, twisting her arm behind her back, then handcuffed her.

“I screamed and screamed. No one came,” she said. “‘You know me,’ I hollered. ‘I live here. I’m Diane Bond.’”

The officers pulled her up off the ground and removed the handcuffs.

Stegmiller put a finger to his lips. He warned her not to say anything about what had happened.

After the officers released her, Diane went to Michael Reese Hospital where she was examined and outfitted with a sling.

The next evening, she encountered Stegmiller outside her building. She was wearing the sling on her right arm. He called out to her in a mocking tone, “What happened toyou?”

Bond fled the building and went to the Stateway Park District field house. Clyde Johnson of the Park District saw that she was in distress. He talked with her and tried to reassure her. A man of considerable personal command, seasoned by sixteen years at Stateway, Johnson was struck by how terrified she was. In a sense, he saw her injury, her trauma.

“It kind of scared me," he recalled. "She was actually shaking. Trembling. She was petrified.”

Johnson noticed she had soiled her pants. He let her take refuge in his office, amid the sports equipment, until the field house closed at 10:00 pm.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on March 30, 2004 and continuing to the present; an interview with Clyde Johnson; and the plaintiff's statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officer Robert Stegmiller denies having any contact with Ms. Bond on the dates alleged.

Bond V. Utreras, et al

On April 12, 2004, the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School filed a federal civil rights suit on behalf of Diane Bond. The suit names as defendants five officers—Edwin Utreras, Andrew Schoeff, Christ Savickas, Robert Stegmiller, and Joseph Seinitz—and the City of Chicago. It claims the defendants violated Bond’s constitutional rights by subjecting her to illegal searches, unlawful seizures, and the use of excessive force. It further claims they were motivated to abuse Bond by her gender and race, in violation of the equal protection provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Illinois Hate Crime Statute.

The Bond suit is the fifth federal civil rights suit that Professor Craig Futterman and his student colleagues at the Mandel Clinic have brought against the Chicago Police Department in recent years as part of an initiative called the Stateway Civil Rights Project. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I helped develop this initiative and initially brought the Bond incidents to the attention of the U of C lawyers.

On April 7, 2005, Futterman filed a motion for permission to amend the complaint to charge that Bond's abuse resulted from systemic practices and policies of the CPD, and to add as defendants Philip Cline, the superintendent of police, Terry Hillard, the former superintendent, and Lori Lightfoot, the former administrator of the Office of Professional Standards. On June 6, the court granted the motion.

The theory of the amended complaint is that the City had a de facto policy of “failing to properly supervise, monitor, discipline, counsel, and otherwise control its police officers,” and further that top police officials were aware “these practices would result in preventable police abuse.” As a result, Futterman argues, members of the skullcap crew knew they could act with impunity. The City and the high officials named in the suit were thus complicit in their abuses.

The case is in the courtroom of Judge Joan Humphrey Lefkow. In the aftermath of the murders of her husband and mother on February 28, Judge Lefkow's cases have been handled by Judge Charles Kocoras, chief judge of the Northern District of Illinois. In mid-July, Judge Lefkow returned to the bench on a limited basis. She is expected to return full-time in the fall.

The City’s defense strategy in Diane Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Edwin Utreras (Star No. 19901), et al is straightforward: each officer denies having had any contact with Diane Bond on any of the dates she claims she was abused. In their reply brief to a motion seeking access to police photos for the purpose of identification, the City attorneys make reference to “the highly unusual and outlandish allegations of abuse in this case” and to “the vague and reckless nature of plaintiff accusations”—language that suggests they will seek to portray Bond as unstable and delusional, that they will argue the abuses she alleges are figments of her imagination.

The City lawyers employ two basic tactics to impeach Bond’s credibility. They stress at several points that she was not arrested, as if this somehow undermines her claims of abuse:

Plaintiff states that although severely victimized and humiliated by the police officers, she was never arrested or taken to a police station as a consequence of her alleged interaction with the police officers. [emphasis added]

The fact she was not arrested is relevant to the issue being addressed in the brief—access to police photos—for the absence of the documentation provided by arrest reports makes identification of the officers involved a central issue. The brief’s phrasing and repetition, however, go beyond that point to imply Bond cannot have been “severely victimized and humiliated by the police officers,” because she was not arrested in any of the incidents. This line of argument contributes to the aura of impunity that is one of the most disturbing aspects of the case. It reminds one uncomfortably of the logic of “disappearances” in Latin America and elsewhere: because there is no arrest, the state has deniability.

The second means by which the City attorneys seek to impeach Bond’s account is to emphasize repeatedly that her physical injuries are inconsistent with her allegations of abuse. For example, with respect to the first incident, they state:

Despite the elaborate description of physical abuse she gave, as of April 15, 2003, plaintiff had only a dime size area of swelling under her right eye for which she sought no medical treatment (See Exhibit C, D, report of OPS investigator Grace Wilson).

The City seeks, in effect, to narrow “abuse” to “physical abuse.” In her OPS interview regarding the April 13th incident, Bond states she was slapped once in the face and kicked once in the side. One sentence of the two-and-a-half page interview is devoted to this physical abuse. The “elaborate description” of abuses that constitutes the bulk of the interview details a series of assaults that caused serious injury without leaving marks on her body. She describes, among other things, having an officer put a gun to her head; witnessing officers destroying her property, including religious objects sacred to her; looking on while officers struck her teenaged son; being forced to disrobe and expose herself under the gaze of a male officer; watching the police beat a man they had brought into her home; and seeing her son and his friend forced to assault that man—to put on a demeaning show for the amusement of the officers—as a condition of release. The injuries inflicted by these abuses were not the kind that could be documented by a trip to the emergency room.

The City’s defense strategy of flat denial necessarily hinges on attacking Bond’s credibility. How far is the City prepared to go down this road? A chilling possibility is that it will seek to use Bond’s history of sexual violence against her. One form this might take would be to argue that the effect of the multiple violations she suffered in her youth has been to make her delusional. Another approach would be to exploit patterns of denial and victim-blaming predictably provoked by cases of sexual violence (especially when multiple incidents are alleged) and argue that she has a history of making unsubstantiated accusations of sexual abuse. Will the City use the acquittal of the five boys charged with raping her thirty years ago for this purpose? Will it offer, in defense of the skullcap crew, that Bond’s own mother didn’t believe her when she blurted out as a small child that her step-father was abusing her?

The Logic of Impunity

The administrative headquarters of the Chicago Police Department seen from a vacant unit at Stateway Gardens.

In one of their briefs, the City lawyers characterize Diane Bond’s allegations as “a series of horrendous acts.” That the alleged acts are serious crimes is not in dispute. The City's thesis is that they did not occur. In one sense, this would seem a difficult defense to sustain, in view of the fact that there are multiple witnesses to three of the four incidents, as well as various documentary records that lend support to Bond’s allegations. In another sense, though, this defense strategy, however problematic on its face, is aided immensely by the larger patterns of denial—by the powerful gravitational field of not-knowing—in which the case arises and will be heard.

Those patterns are at once the central focus of the argument advanced by Bond’s lawyers and the biggest impediment to its success. That argument turns on demonstrating how not-knowing is operationalized and institutionalized. It unfolds in three steps:

The City has “a de facto policy, practice and custom of failing to properly supervise, monitor, discipline, counsel, and otherwise control its police officers.”

The officers who repeatedly violated Bond’s constitutional rights were aware of this “de facto policy, practice and custom.” They knew they could act with impunity.

The City knew its disciplinary and monitoring practices, particularly with respect to repeat offenders, were inadequate. It knew it lacked an effective early warning system. And it knew repeat offenders would, as a consequence, “continue to abuse with impunity.” Its decision not to fix a system it had long known was inadequate and its disregard for the predictable consequences of that decision constitute “conscious, deliberate, and reckless indifference to Ms. Bond’s rights and safety.”

The institutionalization of denial is a complex phenomenon. It is enforced on the ground by the “code of silence” among police officers. It is defended against legal challenges by City lawyers who pursue litigation strategies designed to protect the CPD’s internal processes against any possibility of judicial or public scrutiny. And it is heavily subsidized by the City which pays out millions of dollars each year to settle police misconduct cases that would otherwise go to trial. At its center are the CPD’s investigatory arms—the Internal Affairs Division (IAD), which investigates complaints of corruption and other forms of misconduct not involving the use of force, and the Office of Professional Standards (OPS), which investigates excessive force complaints such as those in the Bond case.

The operation of OPS is partially obscured by secrecy; it lacks transparency as an institution. Much of what is known about it is anecdotal in the sense that it arises out of individual cases. One can only wonder what an independent audit of OPS files would reveal about its internal workings. Through the processes of discovery and ultimately trial, Bond v. Utreras promises to add significantly to our knowledge of how OPS’s investigatory machinery works—and doesn’t work. For the moment, drawing on a variety of sources, it is possible to sketch the broad outlines of that machinery.

As described in the CPD’s annual report, an OPS investigation will have one of four possible outcomes:

Unfounded: “the complaint was not based on facts as shown by the investigation, or the reported incident did not occur."

Exonerated: “the incident occurred, but the action taken by the officer(s) was deemed lawful, reasonable and proper.”

Not sustained: “ the allegation is supported by insufficient evidence which could not be used to prove/disprove the allegation."

Sustained: “the allegation was supported by sufficient evidence to justify disciplinary action.”

The vast majority of complaints are “not sustained.” The reason, according to City representatives, is that many cases turn on the word of the complaining citizen against the word of the officer in the absence of corroborating evidence.

Critics have long questioned how vigorously OPS pursues available leads. For example, Diane Bond’s complaints in connection with the April 13 and April 28 incidents were “not sustained,” despite the fact Bond had provided OPS with physical descriptions of the officers, the license plate of the vehicle they were driving, and the names of witnesses.

In 2003, in Garcia v. City of Chicago, a federal civil rights suit against the City involving allegations of abuse by an off-duty officer, the plaintiff put into evidence OPS investigations of excessive force complaints against off-duty officers over a twenty-one month period. After a jury trial, Judge James Holderman characterized the OPS investigations as “incomplete, inconsistent, delayed, and slanted in favor of the officers.”

OPS has an inherently difficult mission. Police misconduct tends to take place in the shadows. And the darkness is deepened by the “code of silence” among officers. TheBond complaint describes the code:

According to standard practice, police officers refuse to report instances of police misconduct, despite their obligation under police regulations to do so. Police officers either remain silent or give false and misleading information during official investigations in order to protect themselves and fellow officers from internal discipline, civil liability, and criminal charges.

In order to bring misconduct to light, the CPD would need to move aggressively against this institutional culture. It would need to bring a high degree of skepticism to the process and be alert to the gang phenomenon that so often figures in police misconduct. It would need to create incentives and disincentives to encourage cooperation. And it would need to provide meaningful forms of protection for officers who come forward to report on the misconduct of fellow officers.

The CPD does none of these things. OPS uncritically gives corroborative weight to the statements of other officers at the scene. It appears rarely, if ever, to recommend that an officer who witnessed an incident of misconduct by a fellow officer be charged with failure to report a crime. And it is subject to a City policy that bars the CPD from transferring whistleblowers from their units in order to protect them against retaliation. Rather than penetrating the code of silence, OPS practices mesh with it to form a system that seems designed to produce judgments of "not sustained."

Many of the constraints under which OPS operates are dictated by the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), the police union, and are embodied in its contract with the City. For example, OPS is sharply limited in the use it can make of an officer’s prior history of complaints. Complaints alleging criminal conduct are kept for seven years; lesser complaints for five years or in some instances for a year. This makes it difficult for investigators to track patterns of misconduct over time.

The FOP’s aggressive representation of its members in contract negotiations is to be expected. The question is whether concessions to the union enable the City to blunt the effectiveness of internal investigations, while claiming, “The union made us do it.”

During 2001 - 2003, OPS sustained roughly 5% of the 7,613 excessive force complaints it received. Critics have argued that even this small number is inflated. For one thing, OPS sometimes sustains a complaint for reasons other than the brutality charge. For example, investigators may find that the officer did not properly execute the required paperwork, and that becomes the basis for the sustained judgment rather than the original charge of excessive force.

The small number of cases sustained by OPS are then further reduced by the Police Board. Appointed by the Mayor, the Police Board reviews cases in which the superintendent recommends termination or suspension for more than thirty days and cases in which officers appeal suspensions between six and thirty days. (In suspensions of five days or less, there is no appeal.) The Board frequently exonerates the officers brought before it or reduces the penalties against them. It does not have the authority to increase penalties.

Procedural protections and appeal processes are of course justified to protect the rights of officers accused of wrongdoing. The question is whether the procedures of OPS and the Police Board, taken together, do not have the effect of largely crippling the investigatory process.

The character of the City’s machinery for investigating brutality complaints is most tellingly revealed by what it yields. The amended complaint in the Bond case summarizes the results of OPS investigations, after Police Board review, for a three year period:

From 2001 through 2003, the City received at least 7,610 brutality complaints against Chicago police officers. The City imposed meaningful discipline in only 13 of those 7,610 complaints: 6 officers were fired and 7 suspended for 30 days or more. In other words, between 2001 and 2003, a Chicago police officer charged with criminal brutality had only a 0.08 (significantly less than a one in a thousand) chance of being fired, and a 0.17% (less than one-fifth of 1 percent) chance of having any meaningful discipline being imposed.

On the basis of such numbers, it is clear that officers who engage in misconduct have little reason to fear they will be disciplined as the result of an OPS investigation. They have even less reason to be concerned about criminal prosecution. Over the fifteen years prior to the alleged abuse of Bond, roughly 2,500 to 3,000 complaints charging police brutality were made each year. During that period, according to the amended complaint, “there was only one instance of an Illinois state criminal prosecution of a Chicago police officer for brutality committed while on duty, as a result of the Chicago Police Department’s referral of a complaint to the Cook Country State’s Attorney’s Office.”

The City has not yet responded to the argument of the amended complaint that the abuse of Bond resulted from systemic policies and practices of the CPD. In light of what is known about the deficiencies of the CPD’s monitoring and disciplinary system, how will it attempt to counter the conclusion that abusive officers indulge their sadism and corruption with impunity, secure in the knowledge that, if challenged by the citizens they abuse, they can say it never happened and rely on the City’s machinery of denial to protect them?

The Traylor Case

The stunning disparity between the thousands of complaints that come to OPS annually and the handful of disciplinary actions that emerge is one perspective on the quality of its investigations. Another is provided by the occasional legal proceeding against an officer for misconduct. Bond’s lawyers cite several cases in which it was disclosed that the defendant had a thick file of past complaints judged “not sustained” by OPS. Among the most telling is a case that arose out of an incident at Stateway Gardens in the early days of the Stateway Civil Rights Project.

On July 9, 2001, Professor Futterman and several law students were using The View From The Ground office on the ground floor of 3544 S. State to interview witnesses about an incident several months earlier in which police officers had struck a young man with their vehicle and then arrested one of our colleagues, Kenya Richmond, when he attempted to document what had happened. There was a commotion outside. We ran out to State Street and found a middle-aged man on a bicycle pinned against a fence by a police squad car. Two white uniformed officers stood by the vehicle surrounded by a fast growing crowd of curious and in many cases outraged residents. Within a few minutes, the crowd had swelled to about a hundred. We immediately called 911 and set to work documenting the incident.

The name of the man trapped between the police car and fence proved to be Nevles Traylor. He was moaning in pain and distress. According to witnesses, the driver of the squad car—Officer Raymond Piwnicki—had deliberately struck Traylor’s bicycle from behind as he rode across the grounds of the development. Piwnicki had then, they said, jumped out of the vehicle and hit Traylor repeatedly in the head, as his partner—Officer Robert Smith—looked on. Piwnicki and Smith were from the Special Operations Section of the CPD. Among the witnesses were several officers from Public Housing South. I spoke with one of them who was as outraged by the incident as any of the residents I talked with. Another public housing officer exchanged sharp words with Piwnicki, then used wire cutters to extricate Traylor from under the police car.

Eventually, an ambulance came and removed Traylor. He was subsequently charged with felony criminal charges—two counts of possession of a controlled substance with intent to deliver—that required, if convicted, a mandatory minimum sentence of four years and allowed a maximum sentence of fifteen years. Over the next two years, the Mandel Clinic represented him first in the criminal case and then in a federal civil rights suit against Officers Piwnicki and Smith.

In the criminal case, Piwnicki and Smith testified they had observed Traylor engage in a hand-to-hand drug transaction and had undertaken pursuit in the course of which he had fallen off his bicycle. Futterman and his law student colleagues demonstrated that it was physically impossible to see what the officers claimed to have seen from the location roughly a block away where they placed themselves. They argued that the officers struck Traylor with their vehicle in an act of “casual cruelty,” then fabricated evidence and falsely arrested him to cover up their abuse.

In the course of their investigation, Futterman and his students contacted the officer with whom I had spoken at the scene. The officer was sympathetic but apologized to Futterman, “You don’t want me to testify. If I do, I’ll spend the rest of my career paying for it—worrying about friendly fire, worrying that when I call for backup no one will come.” Futterman did not call the officer to testify.

The code of silence, it is important to remember, is not simply a matter of professional solidarity. It is ultimately enforced by violence and fear.

The judge found that Piwnicki and Smith arrested Traylor without probable cause, in violation of his constitutional rights, and dismissed all charges against Traylor. A federal civil rights suit against Piwnicki and Smith was subsequently settled.

The Traylor case provides a revealing glimpse of OPS investigatory practices in several respects:

Despite the presence of dozens of witnesses (including police officers) who observed some part of the incident—an incident that occurred half a block from their office—OPS investigators found the Traylor complaint “not sustained.”

It was disclosed in the course of the trial that Piwnicki had, within the seven years prior to the incident, accumulated fifty-six citizen complaints. Only one of these complaints had been sustained by OPS. Apart from this one instance, the CPD had not disciplined Piwnicki or identified him as needing behavioral intervention.

A Cook County Circuit Court judge having found that Piwnicki and Smith had violated Traylor’s constitutional rights, OPS did not see fit to reopen the complaint for further investigation.

* * * *

What will we learn, as Bond v. Utreras unfolds, about the past history of complaints against members of the skullcap crew? Bond’s lawyers state that crew members “have amassed scores of abuse complaints within four years of their abuse of Ms. Bond.” They do not disclose the precise number of complaints, but those numbers, whatever they are, can be assumed to be depressed for several reasons:

As a general matter, there are strong disincentives to file a complaint. OPS does no active outreach. Citizens cannot complain anonymously. It is standard procedure to disclose the identity of the complaining citizen to the officer named in the complaint. After filing, complainants are required to execute an affidavit affirming under oath that the statements they have given are true. A reasonable requirement on its face, it carries the implied threat, in the context of OPS's record of very rarely sustaining complaints, that complaining might expose one to having the investigation turned against one. Perhaps the biggest disincentive is the knowledge that it is extraordinarily unlikely a complaint will result in meaningful discipline.

Members of the skullcap crew are said by residents to frustrate efforts to identify them, refusing to provide their names and badge numbers. They are well known to members of the community but not by name. Because Bond could not at the time provide their names, her OPS complaints may not even be included in the files of Officers Seinitz, Savickas, Utreras, Schoeff, and Stegmiller.

Victims and witnesses of police abuse say they fear reprisals from the officers who abused them. Several report being threatened. Harold Hall, a public defender who had in the course of his work noticed possible patterns of abuse by members of the skullcap crew, filed a complaint to IAD that Officer Utreras had threatened him. Hall stated that Utreras had approached him in the courtroom and, within the hearing of two Assistant State’s Attorneys, had said, "I hear you've been badmouthing me." Utreras then, according to Hall, delivered a veiled threat. “I better not catch you in my neighborhood” (i.e., the South State Street corridor of public housing), he said. “You know how those traffic stops go.” If a police officer is prepared to threaten an officer of the court in open court, imagine the ease with which he would intimidate residents of an abandoned community such as Stateway Gardens.

How many additional complaints would one find, if one searched the files for street names such as “Macintosh,” or closely correlated the physical descriptions given of unnamed officers with assignment sheets and other available records at the time of the alleged abuses? How many additional complaints would have been made, if citizens had confidence OPS would vigorously investigate them? How many complaints would there be, if victims and witnesses were not vulnerable to intimidation and reprisals?

Despite the many complaints against the crew individually and collectively, Bond’s lawyers assert, crew members have never been disciplined for abuse or identified as in need of intervention. Had the City had an effective monitoring and disciplinary system in place, they argue, members of the crew would never have come to Bond’s door.

“An Excellent Blueprint for Change”

“We’ll use all our resources to go after police officers who engage in misconduct. They are giving a black eye to the majority, the ninety percent of the cops that go out there everyday and put their life on the line to keep this city safe.”

— Superintendent Philip Cline, Chicago Police Department

OPS has amassed a wealth of information—thousands of complaints of excessive force each year—that could provide the basis for a highly effective early warning system. The fact that OPS investigators do not "sustain" most of them does not make these complaints any less useful for this purpose. Patterns of police abuse are not random. It is generally agreed that repeat offenders, who constitute a small percentage of the total police force, commit most of the abuses. The mass of complaints, if they were effectively harvested, would thus yield clear patterns.